What does ‘Being Healthy’ mean?

The main reason people purchase organic products “is to look after my own and my family’s health’’[1] The Soil & Health Association consider that an organic diet, and pesticide free environments create critical foundations that promote and sustain physically healthy lives and provide the resilience to deal with emotional challenges that arise in day to day living.

‘Being healthy’ includes the:

- Capacity to access safe healthy nourishing food, in order to prevent suffering from chronic health problems, mental health and neurological conditions and/or premature mortality.

- Right to avoid toxic chemicals in our urban and rural environments.

- Capacity to heal, or reduce the symptoms and discomfort associated with preventable disease and disability, or infectious diseases.

- Ability to avoid potentially toxic chemical residues in food that can contribute to disease and disorder, and that babies and children are particularly at risk from exposure due to vulnerable developmental windows where they are more at risk than adults.

What does ‘Organic’ mean?

The international organics body, IFOAM, defines organic as follows:

‘Organic Agriculture is a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. Organic Agriculture combines tradition, innovation and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and a good quality of life for all involved.’

The principles embedded in European legislation provide direction for the key tenets of organic agriculture. Organic production is expected to contribute to biodiversity, have high level animal welfare standards and the inputs are either to come from organic production, or be naturally derived. Only low solubility mineral fertilisers are permitted, and GMOs are excluded.[2]

Why do families choose to eat organic food?

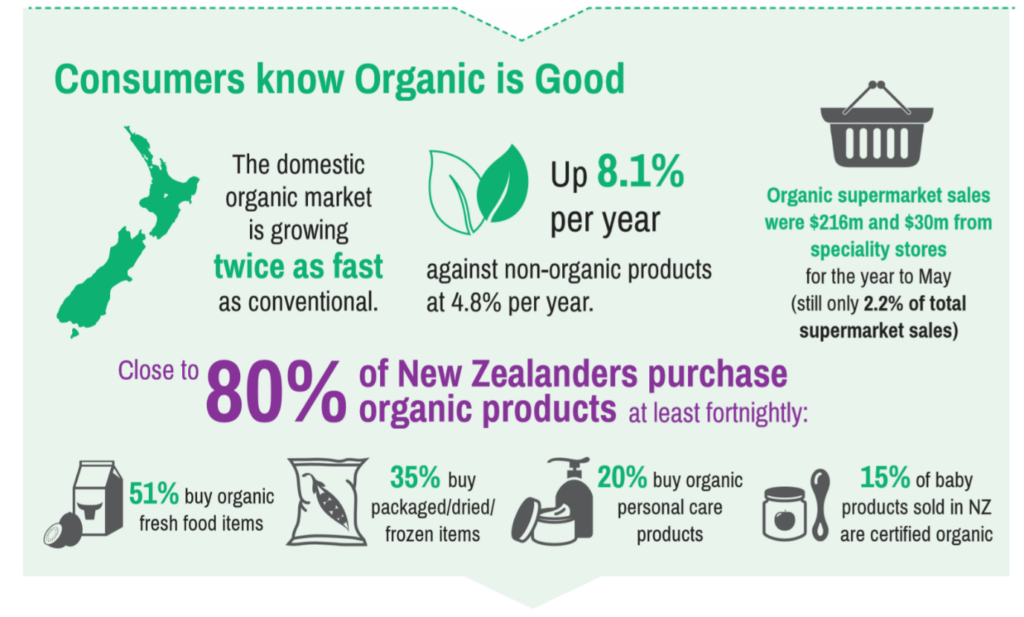

The 2018 New Zealand Organic Sector Report by Organics Aotearoa New Zealand, using data provided by AC Nielsen, provides a snapshot of the New Zealand organic market and consumer preferences. Either natural/chemical free or pesticide/spray free were the dominant expected attributes.[3]

1. OANZ 2018 New Zealand Organic Sector Report p.4

No synthetic chemical inputs.

Consumer avoidance of industrial chemicals, including pesticides, makes sense. An increasing number of scientific studies are demonstrating that commonly used pesticides on food are more toxic than government regulatory studies indicate. The United Nations Special Rapporteur has drawn attention to the fact that children are now born ‘pre-polluted’; that children face an ‘endless stream of exposure, by an invisible cocktail of dozens if not hundreds of hazardous substances, to which they are exposed before and after birth.’[4]

Organic regulation is moderately strict. Organic agriculture systems do not permit the use of synthetic chemicals, and when organic farmers use inputs, these inputs are heavily controlled (for example copper use in organic systems is much more restricted than in conventional systems). Organic food is lower in pesticides, heavy metals and antibiotics. A recent study found that glyphosate formulations, which are applied to many non-organic food crops and applied in urban areas, contain heavy metals.[5] Residues are occasionally found on organic product either from approved or unapproved use or from drift, but residue levels tend to be significantly lower than on conventional (or industrial) food. A European study calculated that because of the overall lower residue profile, consumers have 70 times lower exposure when consuming an organic diet.[6]

Organic demand may be surging because regulatory risk assessment practices that assess and authorise pesticides and chemicals, and define levels of permitted exposure are inadequate to protect human or environmental health.[7] Regulatory risk assessment is riddled with data gaps because of the way agencies operate. First, regulatory agencies rely on data selected and supplied by the industry seeking the approval, and so regulators do not scrutinise other scientific literature to understand new ways pesticides are harmful. This means that regulatory agencies have often not kept up with the latest scientific knowledge and this prevents them from looking at problems from a 21st century perspective. . In the process, the agencies fail to apply established principles of public law, which require them to consider knowledge relevant to the decision at hand. There are, however, few avenues and no resourcing for legal action.[8]

When scientific knowledge falls behind and industry supplies carefully selected data, the risks expand. The following list outlines some of the gaps, which might highlight to some degree, why toxicity and risk is not sufficiently explored and understood:

- Overlapping exposures from different sources and food ingredients not considered;

- Formulation mixtures and individual ingredients in formulations, such as heavy metals, that are individually toxic but ignored in assessment; [9]

- Cumulative exposures – most foods will have multiple different chemical residues; [10]

- Toxicity to the microbiome is ignored;

- Low-dose toxicity is ignored[11] [12]

- The potential for neurodevelopmental toxicity is ignored;

- The problem of hormone level toxicity, how pesticides can disrupt, perturb and mimic hormone function and set the stage for disease and disorder at levels far below those supplied for risk assessment;

- Regulators claim that exposure levels for endocrine- disrupting substances can be arrived at when individual vulnerability cannot be estimated; [13]

- Foetuses and children commonly consume more by bodyweight than adults do and have vulnerable windows of risk. [14] [15] [16]

- The issue that one chemical can harm in multiple ways, and can, for example, simultaneously, be a neurotoxicant, and damage the microbiome and immune system is not considered;

Farming families and farm workers are particularly vulnerable, with agricultural workers more at risk for at around ‘ten serious diseases or functional disorders (leukaemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, prostate cancer, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s, cognitive and fertility disorders, foetal malformations and childhood leukaemia)’ while ‘important suspicion remain for at least four others.’[17] [18]

The problem of regulatory capture, when an industry exerts undue influence over the government authority that is established to regulate that same industry continues to haunt pesticide and biotechnology regulation.

The problem of bias is longstanding. Regulators continue to rely on industry data when conducting authorisation and risk assessment, they exclude independently published data and resist adopting new principles of scientific knowledge as new understandings are arrived at. Risk assessment as it stands currently, cannot address biological and chemical complexity.[19] If lifetime exposure to synthetic chemicals is to be recognised as safe, 21st century scientific knowledge must be incorporated in risk assessment. In addition to data gap issues, scientists are increasingly criticising the incorrect weighting of risk in regulatory assessment and the tendency to exclude or dismiss publicly produced studies. Arbitrary weighting, dismissal of scientific evidence, and a failure to follow established guidelines are not in the public interest. [20] [21] [22]

Nutrition?

Families may buy organic because they believe that organic foods are more nutritious. This, however, is notoriously difficult to measure because it is dependent on many factors, including local conditions, including weather and the skills of the farmer. In addition, any research which indicates that there are measurable nutritional benefits of organic farming[23] is immediately met with scepticism,[24] which is unsurprising given the power of the vested interests involved with industrial farming.

There is, however, some hope that industrial farming has reached such a crisis point in terms of depletion of soils, reduction in biodiversity and pollution of waterways that farmers are now looking for alternatives. The term that is on everyone’s lips is ‘regenerative farming’. It places strong emphasis on building soil organic matter through cover crops, conservation tillage and reducing synthetic inputs.

What is less often acknowledged is that regenerative agriculture is an offspring of organic farming. It was conceived by the Rodale Institute in the US as a system that goes beyond organics. In 2018 a new certification was developed – Regenerative Organic Certification. It uses international organic standards as its baseline requirement but adds important criteria in the areas of soil health and land management, animal welfare and farmer and worker fairness.[25]

Animal Welfare & Antibiotics

Consumers may select organic because of animal welfare issues. Stocking rates are lower, caged animals are prohibited, and the lower levels of synthetic chemicals often mean that disease rates are lower.

Consumers may select organic because of animal welfare issues. Stocking rates are lower, caged animals are prohibited, and the lower levels of synthetic chemicals often mean that disease rates are lower.

In addition, increasing antibiotic resistance is of international concern and industrial agriculture is understood to be a major driver.[26] Many agrichemicals used in conventional agricultural environments act in ways that can reduce the effectiveness of antibiotics.[27] [28] One of these agrichemicals is glyphosate, a herbicide that is patented as an antibiotic[29] Glyphosate can be sprayed on non-genetically modified cereal crops, including wheat, as well as on Roundup-Ready herbicide tolerant crops. This is why dietary studies commonly detect glyphosate on cereals including wheat, oats and barley.[30]

Antibiotic use is prohibited in organic regenerative systems and in addition, synthetic herbicides including glyphosate are not permitted.

Children have higher levels of chemicals in their body

The most compelling evidence of family health benefits from consuming an organic diet rests on the fact that organic diets reduce the levels of pesticides and chemical ingredients used in food production in the body.[31] [32] Diet is the main source of pesticide exposure. Children commonly have higher levels of exposure than adults, as they consume more by bodyweight. An organic diet protects children from exposure.[33]

However, often reviews and studies will ignore the significant role that avoiding pesticides and chemicals play in maintenance of health and wellbeing. [34] [35] Without exploring the absence of chemicals as a driving factor, ‘health and wellbeing’ studies can through this very exclusion, downplay chemical contamination as a driver of ill health.

Many households shift to an organic diet when a family member becomes unwell. The evidence is that it is not the nutritional difference that is the healing factor, but the absence of toxic chemicals. These chemicals can place stress on the immune system, neurological system, microbiome, endocrine system, reproductive system and set the stage for disease and developmental disorder. Many mental health disorders are increasingly associated with diet quality and microbiome integrity.[36] [37] [38]

When people say that ‘health’ is the reason for consuming organic, it can sound a little fuzzy and perhaps, unsubstantiated. A good way to explain what ‘health’ is, perhaps, may be to consider what ‘not health’ is.

The world is experiencing increasing levels of non-communicable (chronic) disease. While there has been a global decline in communicable, neonatal, maternal and nutritional diseases, this improvement is offset by an increasing chronic non-communicable (NCD) disease burden.[39] Populations may be living longer, but they are sicker. Living for years with an illness, or multiple conditions, can be profoundly disabling and distressing, and represents lost potential to societies. Scientists refer to this loss as ‘Disability Adjusted Life Years’ (DALYs).’[40]

An increasing range of studies draw attention to poor dietary patterns that directly contribute to our disease burden. These studies draw attention to the role of processed food; overconsumption of processed cereals, sugars and refined vegetable oils; which can lead to an altered gut microbiota and can contribute to inflammatory diseases and undernutrition.[41] [42] [43] This not only increases disease risk, it can harm mental health.[44]

An increasing range of studies draw attention to poor dietary patterns that directly contribute to our disease burden. These studies draw attention to the role of processed food; overconsumption of processed cereals, sugars and refined vegetable oils; which can lead to an altered gut microbiota and can contribute to inflammatory diseases and undernutrition.[41] [42] [43] This not only increases disease risk, it can harm mental health.[44]

A wide range of chronic health conditions are occurring in people at younger and younger ages.[45] [46] These problems frequently occur as comorbidities (or multi-morbidities) – one person may have osteo-arthritis, depression, and diabetes. A child may have anxiety, chronic ear infections and attention deficit problems. Modern medicine is extremely effective at solving acute health conditions. There is increasing evidence that demonstrates that preventable environmental factors greatly contribute to the chronic disease levels and that dietary interventions can prevent conditions or ameliorate the symptoms of a given problem.

Organic diets are a simple way to navigate the minefield that is modern diet.

Scientists are drawing attention to the intergenerational risk from a single toxic exposure at a time where a person has greater vulnerability. If a pregnant woman carries within her a daughter foetus, that daughter carries within her the ‘grandchildren’ eggs. An adverse toxic chemical exposure has potential to harm three generations. [47] Similarly, toxic chemicals can affect sperm quality. While DNA is not damaged, toxic chemical exposure in a grandparent generation can affect the quality of sperm of grandchildren through epigenetic mechanisms. [48] The idea that chemical exposures in one generation damage future generations raise moral and ethical questions concerning the nature of individual responsibility, and health as a human right. It also raises a question about the ability of vulnerable members of society, such as babies and children to avoid chemical exposure – chemicals are invisible. In addition, intergenerational [49] risk also hints at larger dilemmas relating to national security, and the economic cost of ‘mitigating’, rather than preventing, and medicating increasing rates of chronic disease, when there are mechanisms which exist to protect human resilience and human health for future generations.

However, it is difficult to pinpoint the precise benefits of an organic diet. People consuming predominantly organic food tend to have a healthier lifestyle overall. Organic diets may reduce the risk for obesity and for allergic disease[50], and are recognised to reduce risk of cancer.[51] There are a wide variety of environmental contaminants in the food chain that can act as endocrine disruptors, and increase vulnerability for types of cancer, behavioural problems, immune problems and metabolic disorders.[52] Epidemiological studies have demonstrated the effects of certain classes of pesticides on children’s cognitive development.[53] Healthy hormones are essential for healthy regulation of the metabolism, immune system, fertility and reproduction, growth and development, and sleep and mood.[54] Regulatory agencies approaches to risk when chemicals can interfere with, or mimic hormones are inadequate.[55] These agencies don’t place significant risk weighting on the potential for a worse effect to occur at a lower hormonal level of exposure than at a higher dose which doesn’t act at the level of the hormone. [56] [57] [58]

One size does not fit all.

Our capacity to tolerate poor diets and chemical contaminants in our environment, is dependent on our life stage (babies and children are much more vulnerable); our gender (we are differently vulnerable to different toxins or deficiencies); previous stressors (nutrition, pollution, psychological); and the integrity of our gut microbiome. These factors are interconnected with an individual’s genetic predisposition; epigenetics (chemical and biological pathways that influence and drive genetic expression) and hormone function. The increase in chronic disease cannot be explained by genetics alone, although genetic factors can increase vulnerability to disease. Overconsumption of cheap processed food and lower socio-economic status (reducing access to unprocessed food and protein), are major drivers of undernutrition and obesity in developed countries and high income countries.[59] Family traits and habits can shape family health, and inequality is a major driver of disease and disorder as families vary in their ability to afford nourishing food, and have the time, education or energy to prepare it.

Our capacity to tolerate poor diets and chemical contaminants in our environment, is dependent on our life stage (babies and children are much more vulnerable); our gender (we are differently vulnerable to different toxins or deficiencies); previous stressors (nutrition, pollution, psychological); and the integrity of our gut microbiome. These factors are interconnected with an individual’s genetic predisposition; epigenetics (chemical and biological pathways that influence and drive genetic expression) and hormone function. The increase in chronic disease cannot be explained by genetics alone, although genetic factors can increase vulnerability to disease. Overconsumption of cheap processed food and lower socio-economic status (reducing access to unprocessed food and protein), are major drivers of undernutrition and obesity in developed countries and high income countries.[59] Family traits and habits can shape family health, and inequality is a major driver of disease and disorder as families vary in their ability to afford nourishing food, and have the time, education or energy to prepare it.

Access to safe and nourishing food is a social and health justice issue and children have a right to health.[60] The United Nations Special Rapporteur on human rights and hazardous substances and wastes, Baskut Tuncak, has urged governments and businesses across the world to prevent the widespread childhood exposure to toxics and pollution which has triggered a ‘silent pandemic’ of childhood disease and disability.[61] In his statement to the Human Rights Council, Tuncak drew attention to the fact that health status directly impacts future survival and development – the capacity for that child to develop into a healthy and resilient adult.

Further, an individual’s resilience in dealing with infectious disease appears connected to diet and environment. Environmental exposures are more important than genetic factors in driving immune health.[62] The health of the microbiome, particularly in infancy and early life, appears to play a critical role in the potential for the host to mitigate and contend with infectious disease later in life.[63] [64] However, the biological complexity of the environment, and the absence of scientific resourcing to throw new light on this area, allows the complexities to be dismissed. In the absence of certainty, but with sufficient evidence to indicate diet and the microbiome interact to produce a resilient (or not) individual, action can be taken to limit exposures which create and perpetuate the conditions of impaired immune function.

2 OANZ 2018 New Zealand Organic Sector Report p.4

Whatever the reason for choosing organic, the organic sector is growing strongly; the amount of land recorded as organic continues to increase.[65] In New Zealand annual growth is at 15% and most New Zealanders purchase organic on a regular basis. Organic production is associated with other commensurate benefits: better quality water, safer food chains, and premium markets. It is tourism protective and sends tacit messages out to market sectors of quality and integrity. On a planet challenged by pollution and biodiversity decline and resource limitations, organic production protects freshwater, soil, ecological systems and human health. Yet larger government initiatives to support science that can draw attention to the long-term benefits of organic production are few. This may be because the benefits from organic production are not easily tracked over short-term business or political cycles, and because the benefits are not directly tangible. Polluting activities can be ‘disappeared’ into the environment, equally, activities that do not pollute, are also not easy to equate or reconcile. If governments do not monitor, the public remains ignorant of whether an activity is harmful or beneficial.[66] If governments do not research endocrine disruption and human health, there are no expert scientists to inform the public. Understanding the interdisciplinary, cross-sectorial benefit of organic and regenerative agriculture, as necessary innovation to protect natural resources and food security on behalf of present and future generations, is eminently possible. It requires a rewiring of how we consider ‘innovation’. Agricultural, technical, and medical innovation must be founded on the principle of the kaitiakitanga (stewardship) of human and environmental health.

There are plenty of good scientists, with expertise in predictive analytics, statistical techniques, with knowledge of endocrinology and biological health, with expertise in animal husbandry and soil and crop health, that cannot wait to work together, and work with farmers to explore systems management at the micro and macro level – to completely reframe how we view innovation and to support human and environmental health..

Bibliography

[1] OANZ 2018 New Zealand Organic Sector Report. Organics Aotearoa New Zealand http://www.oanz.org/publications/reports.html

[2] Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 of 28 June 2007 on organic production and labelling of organic products and repealing Regulation (EEC) No 2092/91. Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32007R0834&from=EN

[3] OANZ 2018 New Zealand Organic Sector Report. Organics Aotearoa New Zealand p.7 http://www.oanz.org/publications/reports.html

[4] Tuncat B 2016. Statement of the Special Rapporteur. 33rd session of the Human Rights Council.

[5] Defarge, N., de Vendômois, J., & Séralini, G. (2018). Toxicity of formulants and heavy metals in glyphosate-based herbicides. Toxicology Reports, 156-163

[6] Mie et al 2017. Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: a comprehensive Review. 16:111. DOI 10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4 p.6

[7] Iorns, C. (2018). Permitting Poison: Pesticide Regulation in Aotearoa New Zealand. EPLJ, 456-490.

[8] Joseph, P. (2014). Constitutional and Administrative Law in New Zealand, 4th Ed. Wellington: Thomson Reuters.

[9] Mesnage, R., & Antoniou, M. (2018). Ignoring Adjuvant Toxicity Falsifies the Safety Profile of Commercial Pesticides. Frontiers in Public Health, 361.

[10] Kortenkamp, A., & Faust, M. (2018). Regulate to reduce chemical mixture risk. Science, 224-226.

[11] Zoeller, R., & Vandenberg, L. (2015). Assessing dose–response relationships for endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs): a focus on non-monotonicity. Environmental Health, 2-5.

[12] Vandenberg, L., Colborn, T., Hayes, TB, Heindel, J., Jacobs, D., . . . Zoeller, R. (2013). Regulatory Decisions on Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals Should be Based on the Principles of Endocrinology. .38:1-5. Reprod Toxicol(38), 1-5.

[13] Demeneix, B., & Slama, R. (2019). Endocrine Disruptors: from Scientific Evidence to Human Health Protection. requested by the European Parliament’s Committee on Petitions. PE 608.866 – March 2019. Brussels: Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs.

[14] Watts, M. (2013). Poisoning our Future: Children and Pesticides. Auckland: Pesticide Action Network Asia and the Pacific. Retrieved from https://www.panna.org/resources/poisoning-our-future-children-and-pesticides

[15] Landrigan, P., & Goldman, L. (2011). Children’s Vulnerability To Toxic Chemicals: A Challenge And Opportunity To Strengthen Health And Environmental Policy. Health Aff, 842-50.

[16] Trasande, L. (2019). Sicker, Fatter, Poorer: The Urgent Threat of Hormone-Disrupting Chemicals to Our Health and Future . . . and What We Can Do About It. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

[17] : Aubert, P.M., Schwoob, M.H., Poux, X. (2019). Agroecology and carbon neutrality in Europe by 2050: what are the issues? Findings from the TYFA modelling exercise. IDDRI, Study N°02/19.

[18] Gerage JM et al 2017. Food and nutrition security: pesticide residues in food. Nutrire. 42:3 DOI 10.1186/s41110-016-0028-4

[19] Iorns, C. (2018). Permitting Poison: Pesticide Regulation in Aotearoa New Zealand. EPLJ, 456-490.

[20] Robinson C, Portier CJ et al 2020. Achieving a High Level of Protection from Pesticides in Europe: Problems with the Current Risk Assessment Procedure and Solutions. European Journal of Risk Regulation. doi:10.1017/err.2020.18. https://bit.ly/2xYwIgh

[21] Douwes, J., ‘t Mannetje, A., McLean, D., Pearce, N., Woodward, A., & Potter, J. (2018). Carcinogenicity of glyphosate: why is New Zealand’s EPA lost in the weeds? New Zealand Medical Journal, 82-89.

[22] Clausing P. 2019. Chronically Underrated? A review of the European carcinogenic hazard assessment of 10 pesticides: Pesticide Action Network (PAN) Germany and the Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL) in October 2019

[23] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/higher-antioxidant-and-lower-cadmium-concentrations-and-lower-incidence-of-pesticide-residues-in-organically-grown-crops-a-systematic-literature-review-and-metaanalyses/33F09637EAE6C4ED119E0C4BFFE2D5B1

[24] https://theconversation.com/organic-food-is-still-not-more-nutritious-than-conventional-food-29233

[25] https://rodaleinstitute.org/why-organic/organic-basics/regenerative-organic-agriculture/

[26] Mie et al 2017. Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: a comprehensive Review. 16:111. DOI 10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4

[27] Kurenbach et al. (2018), Agrichemicals and antibiotics in combination increase antibiotic resistance evolution. PeerJ 6:e5801; DOI 10.7717/peerj.5801

[28] Kurenbach, B., Marjoshi, D., Amabile-Cuevas, C.F., Ferguson, G.C., Godsoe, W., Gibson, P. and Heinemann, J.A. 2015. Sub-lethal exposure to commercial formulations of the herbicides dicamba, 2,4-D and glyphosate cause changes in antibiotic susceptibility in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mbio 6, e00009-00015.

[29] Mesnage R. and Antoniou M 2017. Facts and Fallacies in the Debate on Glyphosate Toxicity. Frontiers in Public Health. 5:316

[30] FSANZ 2019. 25th Australian Total Diet Study. June 2019. Appendix 1. https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/publications/Pages/25th-Australian-Total-Diet-Study.aspx

[31] Hyland C et al 2019. Organic diet intervention significantly reduces urinary pesticide levels in U.S. children and adults. Environmental Research. 171:568-575

[32] Curl et al 2019. Effect of a 24-week randomized trial of an organic produce intervention on pyrethroid and organophosphate pesticide exposure among pregnant women. Environment International. 132:104957

[33] Barrett JR. OP Pesticides in Children’s Bodies: The Effects of a Conventional versus Organic 2019diet. Environmental Health Perspectives 114:2 A112

[34] Apaolaza V et al 2018. Eat organic – Feel good? The relationship between organic food consumption, health concern and subjective wellbeing. Food Quality and Preference. 63:51-62

[35] Janssen M. 2018. Determinants of organic food purchases: Evidence from household panel data. Food Quality and Preference. 68:19-28

[36] Foster, J. A., Rinaman, L., & Cryan, J. F. (2017). Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiology of Stress, 124-136.

[37] Martin, C., Osadchiy, V., Kalani, A., & Mayer, E. (2018). The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 133-148.

[38] Stahl, S., Albert, S., Dew, M., & al, e. (2014). Coaching in healthy dietary practices in at risk older adults: a case of indicated depression prevention. Am J Psychiatry, 499-505.

[39] Kassebaum et al 2016. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388: 1603–58

[40] Roser M., Ritchie H. Burden of Disease. https://ourworldindata.org/burden-of-disease

[41] Rico-Campà etal 2019. Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and all cause mortality: SUN prospective cohort study. BMJ 2019;365:l1949

[42] Zinöcker MK. & Lindseth IA. The Western Diet–Microbiome-Host Interaction and Its Role in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients.10:365: ; doi:10.3390/nu10030365

[43] Korach-Rechtman et al 2020. Soybean Oil Modulates the Gut Microbiota Associated with Atherogenic Biomarkers. Microorganisms 8(4), 486; https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8040486

[44] Rucklidge, J., & Kaplan, B. (2016). Nutrition and Mental Health. Clinical Psychological Science, 1082-1084.

[45] Van Cleave J, Gortmaker SL, Perrin JM. DYnamics of obesity and chronic health conditions among children and youth. JAMA. 2010;303(7):623–30. pmid:20159870

[46] Perrin JM, Bloom SR, Gortmaker SL. The increase of childhood chronic conditions in the United States. Jama. 2007;297(24):2755–9. pmid:17595277

[47] Lamoureaux, J. (2016). What if the Environment is a Person? Lineages of Epigenetic Science in a Toxic China. Cultural Anthropology, 188-214.

[48] Kubsad, D., Nilsson, E., King, S., Sadler-Riggleman, I., Beck, D., & Skinner, M. (2019). Assessment of Glyphosate Induced epigenetic transgenerational Inheritance of pathologies and sperm epimutations: Generational toxicology. Nature Scientific Reports, 9, 6372. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42860-0

[49] Nilsson, E., Sadler-Riggleman, I., & Skinner, M. (2018). Environmentally induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of disease . Environmental Epigenetics, 1-13.

[50] Mie et al 2017. Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: a comprehensive Review. 16:111. DOI 10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4

[51] Baudry J., et al 2018. Association of Frequency of Organic Food Consumption With Cancer Risk. Findings From the NutriNet-Santé Prospective Cohort Study. JAMA Internal Medicine, 10.

[52] Nordic Council of Ministers 2018. New EU criteria for endocrine disrupters Consequences for the food chain. TemaNord 2018:537. Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen.

[53] Attina, T., Hauser, R., Sathyanarayana, S., Hunt, P., Bourguignon, J., Myers, J., . . . Trasande, L. (2016). Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the USA: a population-based disease burden and cost analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016; 4: 996–1003. Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, 996-1003.

[54] Trasande, L. (2019). Sicker, Fatter, Poorer: The Urgent Threat of Hormone-Disrupting Chemicals to Our Health and Future . . . and What We Can Do About It. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

[55] Slama, R., Bourguignon, J.-P., Demeneix, B., Ivell, R., Panzica, G., Kortenkamp, A., & Zoeller, R. (2016). Commentary: Scientific Issues Relevant to Setting Regulatory Criteria to Identify Endocrine-Disrupting Substances in the European Union. Environmental Health Perspectives, 1497-1503.

[56] Dr. A. Kortenkamp et al, “State of the Art Assessment of Endocrine Disruptors” (2012), available from http://ec.europa.eu/environment/chemicals/endocrine/pdf/sota_edc_final_report.pdf

[57] Vandenberg LN. 2019. Endocrine Disruptors and Other Environmental Influences on Hormone Action. The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology and Behavioral Endocrinology. Eds Welling LM & Shackelford TK.

[58] Leemans et al 2019. Pesticides With Potential Thyroid Hormone-Disrupting Effects: A Review of Recent Data. Front. Endocrinol

[59] Perez-Escamilla et al. 2018. Nutrition disparities and the global burden of malnutrition. BMJ 2018;361:k2252

[60] UNHR. 1990. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Adopted by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989 entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with article 49

[61] Tuncat B 2016. Statement of the Special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes at the 33rd session of the Human Rights Council . https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=20576&LangID=E

[62] Brodin et al 2015. Variation in the Human Immune System Is Largely Driven by Non-Heritable Influences. Cell. 160:1-2;37-47

[63] Bloomfield SF et al 2016. Time to abandon the hygiene hypothesis: new perspectives on allergic disease, the human microbiome, infectious disease prevention and the role of targeted hygiene. Perspectives in Public Health 136:4;213-224.

[64] Thaiss et al 2016. Review article: The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature. 535:65–74

[65] FIBL and IFOAM The World of Organic Agriculture: Statistics and Emerging Trends 2019 https://www.organic-world.net/yearbook/yearbook-2019/pdf.html

[66] Aotearoa New Zealand Policy Proposals on healthy waterways: Are they fit for Purpose? (2019). The Soil and Health Association of New Zealand and Physicians and Scientists for Global Responsibility Charitable Trust New Zealand Wellington, ISBN 978-0-473-50130-3